A computer vision specialist from Microsoft gave a deep dive into the challenges and opportunities of its HoloLens in a keynote at the Embedded Vision Summit here. His talk sketched out several areas where such augmented reality products still need work to live up to their promise.

The HoloLens “will be the next generation of personal computing devices with more context” about its users and their environments than today’s PCs and smartphones, said Marc Pollefeys, an algorithm expert who runs a computer vision lab at ETH Zurich and joined the HoloLens project in July as director of science.

Jeff Bier, host of the event and founder of the Embedded Vision Alliance, praised the headset as “one of the first AR and VR products that didn’t give me a splitting headache” but said that the $3,000, 1.2-pound developer version available today “needs to get smaller and cheaper.”

Microsoft has not revealed when it will upgrade the headset. It has announced plans to release later this year a lower-cost version with four, rather than two, cameras that can be plugged into a Windows 10 PC to run virtual reality apps with head tracking.

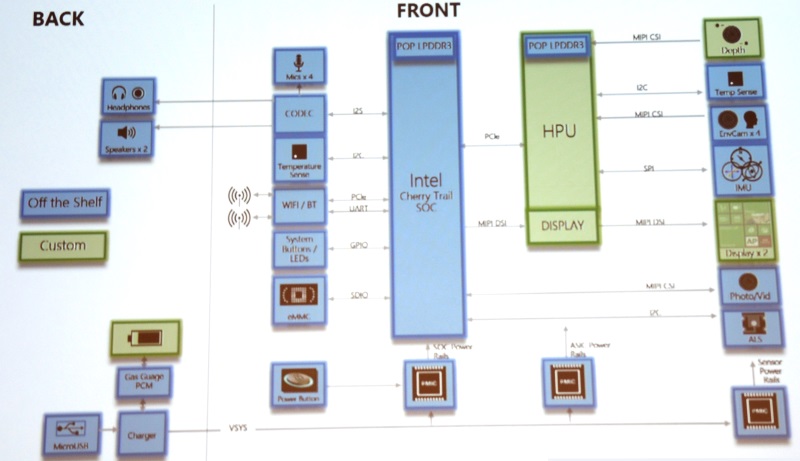

It could take a decade to get to the form factor of Google Glass, Pollefeys said. “There are new display and sensing technologies coming … and a lot of trade-offs in how much processing we ship off [the headset to the cloud, and] we are going from many components to SoCs.”

One of the team’s biggest silicon challenges is to render “the full region and resolution that the eye can see in a lightweight platform.”

“Most of the energy is spent moving bits around … so it would seem natural that … the first layers of processing should happen in the sensor,” Pollefeys told EE Times in a brief interview after his talk. “I’m following the neuromorphic work that promises very power-efficient systems with layers of processing in the sensor — that’s a direction where we need a lot of innovation — it’s the only way to get a device that’s not heavier than glasses and can do tracking all day.”

The 3D maps that the headsets can generate are best rendered with floating-point math. Pollefeys would not say whether Microsoft uses that approach or whether the cloud services that it uses to build and maintain maps use GPUs.

Microsoft uses cloud services to automatically stitch together multiple maps that headsets create as users walk through buildings, Pollefeys said, noting one map of a building at its headquarters that was created by 100 sessions. “Every floor of the building looks the same, so maps can get confused: Third or fourth floors can wind up with mismatches and wormholes connecting places that shouldn’t be connected.”

The current headset uses Wi-Fi signals to gather some location data, but it does not have a GPS. In general, Microsoft is “still experimenting” with how much processing it wants to do on the headset versus the cloud. The device targets indoor use so far to avoid challenges creating virtual holograms in daylight.

Next page: Building up third-party apps and services

----Form EE Times